As Windows 2000 was being developed in the second half of the 1990s, Microsoft was firmly focused on building in as much functionality as possible, in a play to push Novell Netware aside and establish Windows NT as the operating system for the business world. When NT was released to manufacturing ten years ago, it was well-received by reviewers, businesses, and enthusiasts alike, and for much of the decade the OS has been considered by some to be the pinnacle of Windows releases. Its headline business features—Active Directory, Group Policy, Internet Information Services, Management Console, Windows Management Instrumentation—have become industry standards. But most importantly, Windows NT served as the technological basis for what can fairly be described as the most successful and well-known software product of all time: Windows XP.

But there’s always been a dirty little secret hiding underneath that iconic field of green grass. From an engineering and security standpoint, the foundation of Windows 2000 and Windows XP is absolutely horrible.

The many security shortfalls of Windows have been discussed at length over the years. Terms like “Nimda,” “Code Red,” and “Messenger Service” can still give battle-hardened IT administrators involuntary twitches. Malware evolved from being the hobbyhorse of bored teenagers into being a profitable industry. It was the sorry state of security that led Microsoft Chairman Bill Gates to announce a company-wide "Trustworthy Computing" initiative; he told the company's software developers that "when we face a choice between adding features and resolving security issues, we need to choose security. This resulted in Windows Vista and Server 2008 being delayed by years, so that Microsoft could focus instead on fixing many of the worst security problems in Windows XP and Server 2003. While the improvements made in XP Service Pack 2 such as the on-by-default firewall, less permissive Internet Explorer, and tightened permissions were both necessary and welcome (despite the slow uptake), it didn’t take long for it to become obvious that Windows had received first aid, not surgery—the rate at which new security vulnerabilities were found barely abated. Even now, more than five years since the release of XP SP2, the rate at which new security vulnerabilities are found remains steady.

Microsoft’s problems with Windows development extended well beyond security. By the time Windows Server 2003 was released, Microsoft had come to accept that while it was pretty good at producing a fully-featured NT-based operating system with an extensive graphical user interface, it was wholly unable to produce a fully-featured NT-based operating system without one. Evidence of reliance on the presence of a graphical user interface can be seen all through older Windows 2000 and Windows XP. For example, there were no command-line tools to configure and install patches and software from Windows Update, nor was it even possible to select the updates to install without using Internet Explorer. Another problem was the tendency of some low-level system services to present graphical interfaces to the user, and to make use of code inside of DLLs that were primarily concerned with displaying a user interface. Worse still for Microsoft’s thousands of Windows developers, Windows had become such a large project that it was extremely difficult for any group to make changes to one part of the system and know exactly how those changes would affect the rest of the system.

Readers who are familiar with Windows Embedded (and third-party tools like nLite) are probably scratching their heads right about now, wondering what all the fuss is about. Hasn’t the ability to build a small version of Windows for a specific purpose been around for a very long time? Yes, it has, but the approach used by these tools is roughly equivalent to taking a hacksaw to a large Persian rug in order to make it fit in a smaller room. Sure, it’s still a rug, but it’s a pretty nasty way of getting the job done. Windows Embedded, nLite, and similar tools simply chop the unwanted DLL files from the system, twiddle a few things here and there in the Registry, and call it a day. With Windows Embedded, this may not be such a bad approach, because the intended purpose of Windows Embedded is to run a single application, such as a kiosk, ATM, or outdoor display. But for a general-purpose operating system, it’s just not an option.

Getting to the Core of the problem

With these problems in mind, Microsoft assembled a team of core operating system architecture experts that were tasked with mapping out the many interdependencies between the 5,500+ components of Windows, and devising a plan to separate them into “layers.” The lowest layer would become a self-contained system that has no understanding of, or dependence on, the large majority of Windows. Successive layers would include more functionality, but would only be dependent on layers underneath it. This project, which was underway by the end of 2003, was given an internal name of “MinWin.”

The first real manifestation of this componentization effort was the Windows Server Core installation option in Windows Server 2008. The Server Core pitch is simple and compelling enough—it’s still Windows, but without the vast majority of the desktop components that have no place on a dedicated server. You get something that can still run your Active Directory domain controllers, your file shares, and your DNS servers, without having to be bothered by installing patches for Internet Explorer, Windows Media and a host of other components that were welded into prior releases of Windows. Fully two-thirds of the security patches released for Windows Server 2003 offered no actual increase in security for dedicated servers, but still required software to be installed and reboots to be performed on a near-monthly basis.

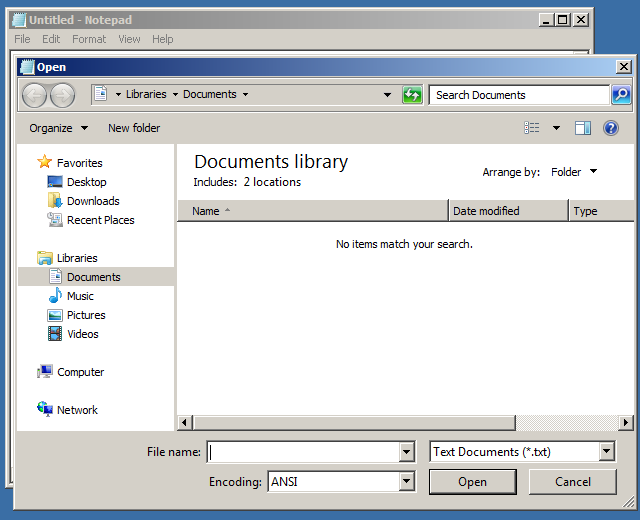

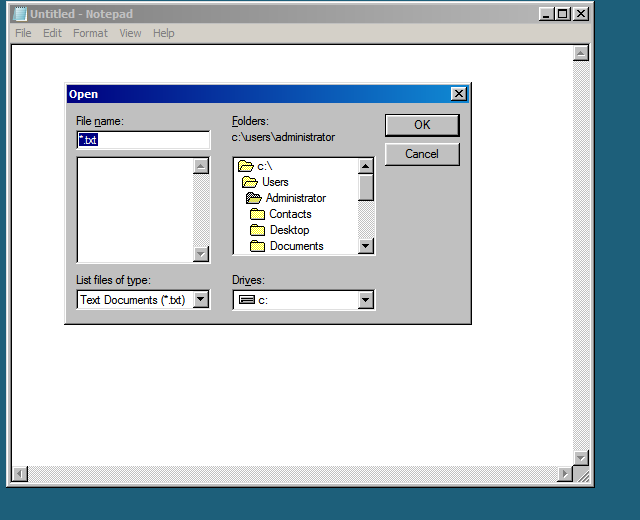

When you install Server Core, you are greeted with the familiar Windows login screen, complete with high-resolution graphics. Log in, and you’re presented with a command prompt. Server Core in 2008 R2 is a vast improvement on 2008 in this area; just type “sconfig” and you can step through some simple menus to configure networking, remote management, Windows Update, and domain participation. A couple of graphical applications and configuration panels like Notepad, Task Manager, and Date and Time are still present, but all other tasks on the machine must either be done through command-line utilities, or via remote management. What is offered in terms of UI capabilities is very basic. Because Windows Explorer and many of the components of the Shell aren’t included in a Server Core install, applications like Notepad, which would normally show an “Open” dialog box like this:

instead looks like this:

Yes, that’s really the Open dialog that was introduced with Windows 3.1 in 1992! Printing doesn’t work because there is no print subsystem. Help doesn’t work, either, because neither the help files nor the help engine are installed. Twelve fonts are available instead of the 50 or so that a full Server 2008 install will have.

Sounds good so far, yes? There’s a big problem—a Server 2008 Core installation, without any installed roles or extra features, still has disk and memory requirements that handily exceed a full Windows 2000 install. Server 2008 R2’s memory consumption is somewhat lower (I estimate about 30% lower than Server 2008 before roles and features are installed), but disk requirements remain high. Microsoft says there are still about 600 interconnected DLLs and other binaries, totaling hundreds of megabytes. None of these could be safely removed without causing other parts of the system to break. Even Mark Russinovich, widely regarded as one of the world’s top experts on Windows internals, admits that they still can’t predict what exactly would break.

Clearly, if Microsoft wants to demonstrate that its idea of a “slimmed-down” server operating system resembles something a bit smaller than, say, Canada with the northern territories chopped off, there is still a lot more to be done.

reader comments

130